|

English

Japanese 中文 한국어

12 minutes movie to get brief understanding of what

really happened.

Photos of Nanking

Under the Japanese Occupation

(Click for

larger image)

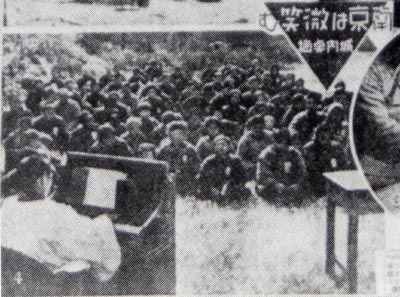

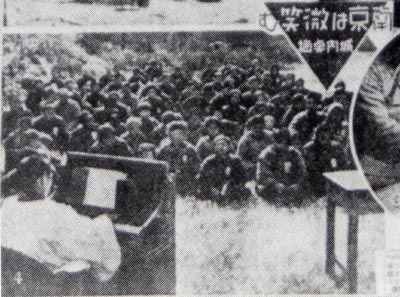

After the battle, many Nanking citizens, who had abhorred bad deeds done by

the Chinese military in the city, welcomed the Japanese military. This is a

photo of Japanese soldiers and the Nanking citizens giving cheers, on the day

of the Japanese military’s ceremonial entry into Nanking (Dec. 17, 1937, 4

days after the fall of Nanking). The citizens are wearing armbands of the

flag of Japan, which were given to all civilians of Nanking to distinguish

them from hiding Chinese soldiers in civilian clothing. (“Sino-Japanese War Photograph

News #15,” the Mainichi Shimbun

newspaper, published on Jan. 11, 1938)

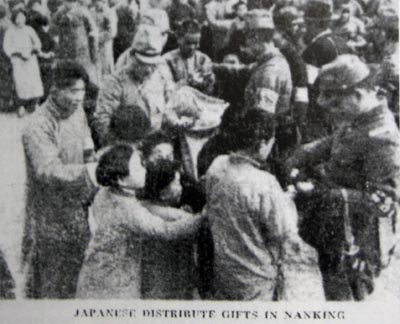

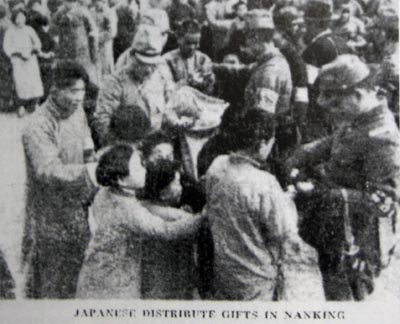

Japanese

soldiers distributing gifts to Chinese citizens in Nanking.

Photo from the British newspaper North China Daily News, published in China

in English on December 24, 1937, eleven days after the

Japanese occupation of Nanking

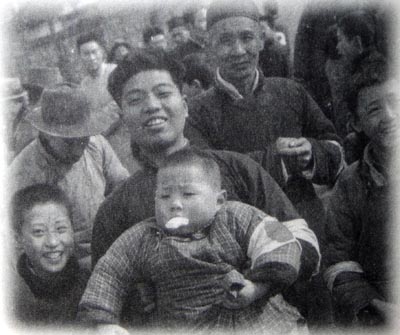

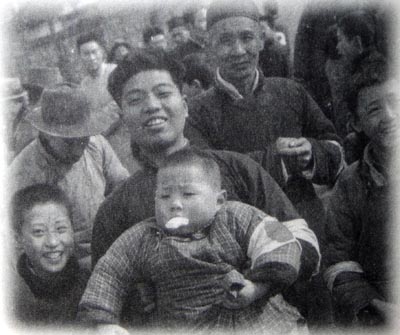

Japanese

soldiers playing with Chinese children in Nanking using toys, and their

parents wearing armbands of the flag of Japan. Photo taken on Dec. 20, 1937,

seven days after the occupation, and published in the pictorial book, Shina-jihen Shasin Zensyu, in 1938.

The Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun, published on Dec. 18, 1937, five days after the

occupation, reported scenes of the city in the article

entitled, “Nanking

in Restoring Peace”:

(Right) Japanese soldiers buying from a Chinese;

(center top) Chinese farmers who returned

to Nanking cultivating their fields;

(center bottom) Chinese citizens returning to Nanking;

(left) Street barbershop, Chinese adults and children smiling.

The Asahi Shimbun, published on

Dec. 21, 1937, eight days after the Japanese occupation, reported

scenes of Nanking in the article entitled, “Kindnesses to Yesterday’s Enemy”:

(Right top) Chinese soldiers under medical treatment;

(left top) Chinese soldiers receiving food from a Japanese;

(center) Japanese soldiers buying at a Chinese shop;

(right bottom) Chief Yamada talking with a Chinese leader;

(left bottom) Chinese citizens relaxing in Nanking city

Chinese

people sick or wounded in a hospital in Nanking

and Japanese medics nursing them. Photo from the North China

Daily News on December 18, 1937, five days after the occupation of Nanking.

Japanese

soldiers nursing Chinese wounded soldiers. Photo taken in Nanking

on December 20, 1937, seven days after the occupation, by

the correspondent Mr. Hayashi; placed in the Japanese pictorial magazine, Asahi-ban Shina-jihen

Gaho, and published on January 27, 1938.

“The Chinese citizens did not fear the Japanese and willingly cooperated with

me for photo-taking,” testified the press photographer Shinju Sato. Photo

taken in Nanking Safety Zone on December 15, 1937, two days after the

occupation of Nanking.

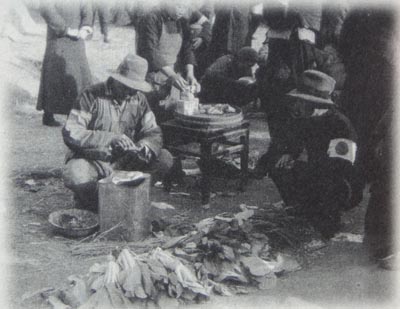

Nanking citizens with armbands of the flag of Japan selling vegetables on the

street on December 15, 1937.

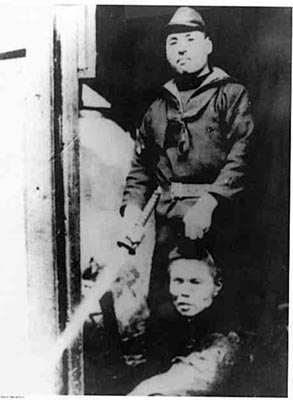

Chinese boy smiling and Second Lieutenant Takashi Akaboshi, who led a fight

along the Yangzi River. Photo taken near the walls of Nanking

just after the Japanese occupation (courtesy of

Takashi’s wife).

When Japanese soldiers distributed food and sweets, Chinese adults and

children gathered together. (December 18, 1937, in Nanking.

From the Tokyo Nichinichi

Shimbun.)

Japanese

medics giving treatments to Chinese children in Nanking

for plague prevention. Photo taken on December 20, 1937, seven days after the

occupation, by the

correspondent Hayashi. (From Asahi

Graph, book 30, No. 3, published on January 19, 1938.)

Chinese citizens rejoicing to receive confectionery from Japanese soldiers on

December 20, 1937, in Nanking. (From Asahi-ban Shina-jihen

Gaho, published on January 27, 1938.)

Chinese

prisoners of war going home smiling. From Japanese pictorial book, Asahi-ban Shina-jihen Gaho, “Scenes We

Want to Show to Chiang Kai-shek,” published on August 5, 1939.

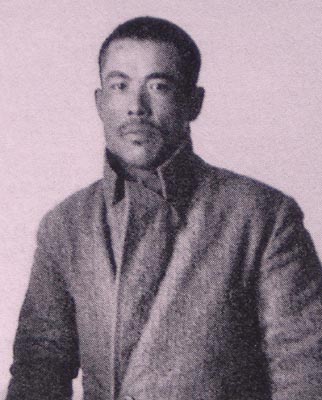

Liu Qixiong, a Chinese soldier who was hiding in

the Nanking Safety Zone and caught as a POW. He was used as a coolie for a

while, but later became the commander of a brigade for Wang Jingwei’s

pro-Japanese government. (Asahi-ban

Shina-jihen Gaho, No. 14, January 1, 1938)

Japanese

soldier handing paper money to a Chinese family in the

Nanking Safety Zone. Photo taken on December 27, 1937, fourteen days after the

Japanese occupation, by the correspondent Mr. Kageyama; from Asahi-ban Shina-jihen

Gaho, published on January 27, 1938.

Chinese

merchants selling to Japanese soldiers in Nanking.

Photo from the pictorial magazine Mainichi-ban

Shina-jihen Gaho, published on February 1,

1938.

Chinese Christians having worship service in Nanking

with Reverend John Maggie, American pastor, after peace returned to the city.

Photo from the Asahi Shimbun

newspaper published on December 21, 1937, eight days after the Japanese

occupation, in the article entitled “Nanking Smiles.” The article stated,

“Hearing their hymns, we noticed, ‘Oh, today’s Sunday.’”

Chinese

women coming out of

an air-raid

shelter and protected by the Japanese military. Photo taken on December 14, 1937,

the day after the fall of Nanking, by the correspondent Kadono,

and published in the Asahi Shimbun

on December 16, 1937.

Chinese people hired by Japanese soldiers to carry food. Photo taken on

January 20, 1938, in Nanking. The Japanese

distributed the food to the citizens, and there was no death by starvation in

Nanking. (From Shina-jihen Shashin Zenshu

(2).)

Chinese prisoners of war with legs or arms cut off recuperating in Nanking

Concentration Camp in early spring of 1938.

(From Mainichi Graph - Nihon no Senreki.)

Chinese prisoners of war playing music with handmade instruments in Nanking

Concentration Camp (Mainichi-ban Shina-jihen

Gaho, No. 59, May 20, 1939.)

Citizens celebrating the start of Nanking’s self-government on January 3,

1938, waving the Japanese flag and the Chinese five-color flag.

Forged Photos of the “Massacre”

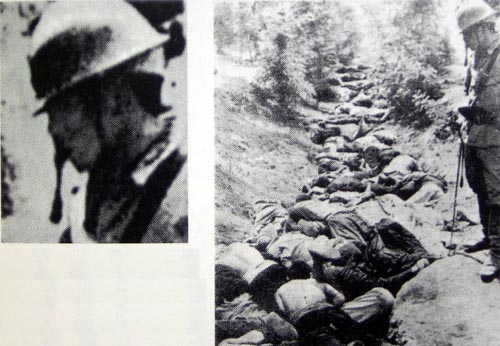

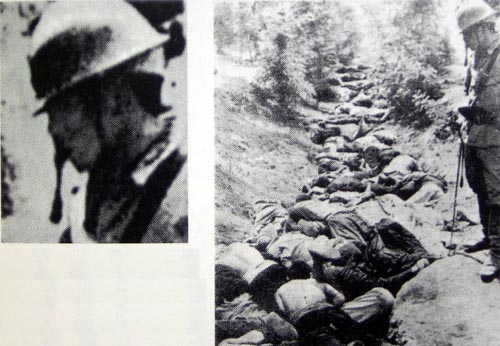

Iris Chang’s book, The Rape of Nanking,

dated this photo as having been taken just after the Nanking Massacre.

However, the alleged Japanese soldier standing by wears a military uniform

with a turned-down collar with class badges on it. This style was not

introduced until after the uniform revision on June 1, 1938. In addition, the

photo does not tell how the pictured dead were killed, by massacre or in

battle, and there were many Chinese soldiers in ordinary clothes.

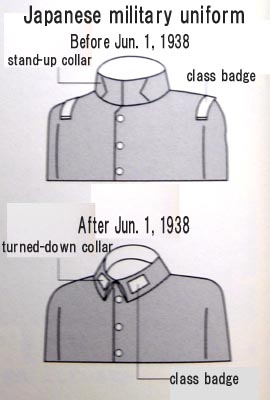

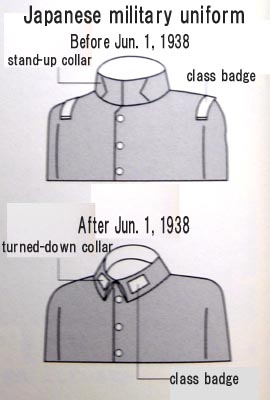

Design of Japanese Army uniforms before and after the June 1, 1938 revision.

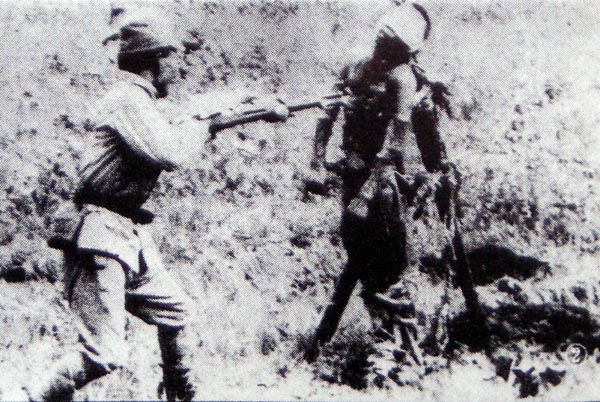

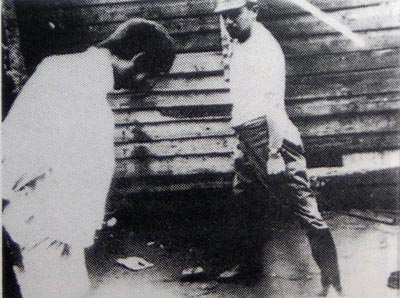

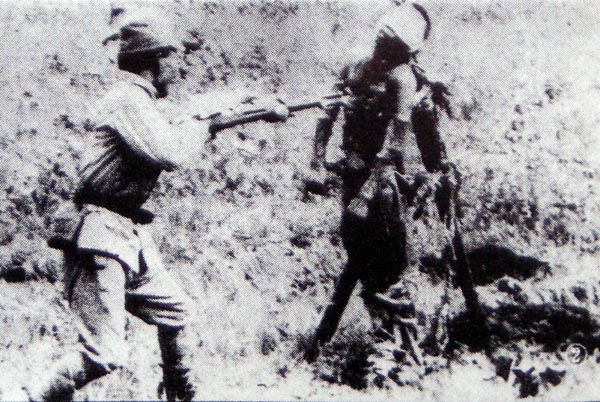

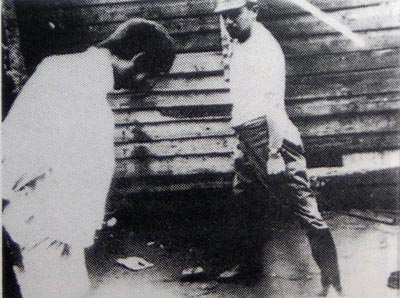

In the fall of 1937, the Associated Press (AP) distributed this photo

as a Japanese soldier using a Chinese national as a guinea pig for bayonet

practice. Iris Chang’s The Rape of

Nanking carries the same kinds of photos of Japanese atrocities. However,

the soldier wears a turned-down-collared uniform, which no Japanese soldier

wore at that time, so the man is not a Japanese soldier. The January 1939

issue of Lowdown, an American magazine, commented about these photos

that this was in fact a communist Chinese officer torturing a Chinese

prisoner.

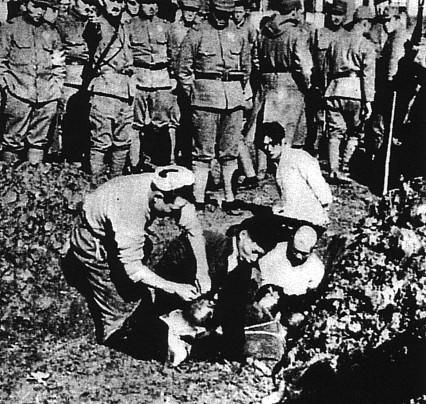

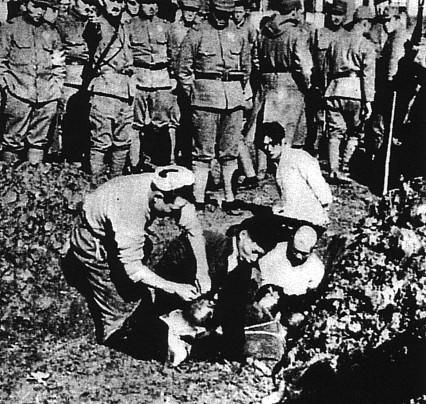

This photo is explained as Chinese people buried alive by the Japanese as a

part of the Nanking Massacre. However, the Japanese soldiers are not

threatening the Chinese with guns. The Chinese look like they are going in

willingly. And the color of true Japanese military gaiters were similar to

their uniforms, whereas the gaiters in the photo are rather white—the color

of Chinese military gaiters. Also, the size of each person is unnatural.

Professor Higashinakano concludes that this was a

composite of plural photos.

This is not a photo of Japanese soldiers but Chinese soldiers buring Chinese civilians. The idea of buring

civilians alive was not Japanese but Chinese.

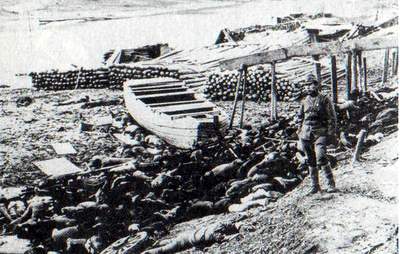

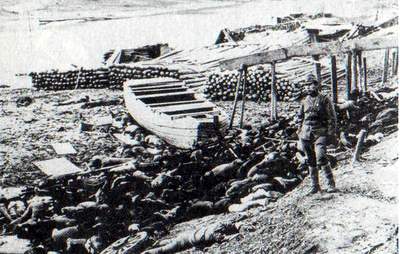

This photo was identified as Nanking Massacre victims on the shore of the

Yangtze River, but these bodies were the Chinese soldiers who died in battle,

not a massacre. Hashimoto, a Japanese soldier who fought there, testified,

“The Chinese soldiers carried their rifles or machine-guns but none of them

were in regular military uniform.” Sekiguchi also testified, “None of them

showed signs of surrender.” Thus, the Japanese army had to continue to attack

them and many of the Chinese soldiers were shot or drowned in the river. In

this photo are the bodies that were washed up on shore.

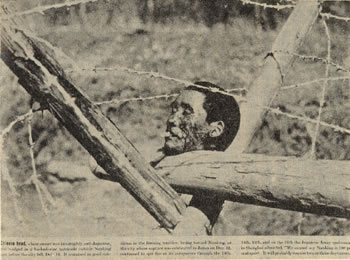

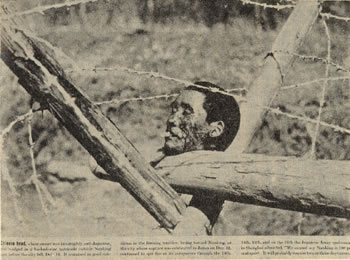

This photo is used as purported evidence of Nanking Massacre victims, but

there was no such custom of gibbeted heads among the Japanese after the

1870s. Among the Chinese, however, this custom was still observed in the

1930s, and several photos of gibbeted heads appeared in cities of China

in those days. Chinese Nationalists and Communists often killed pro-Japanese

Chinese people and gibbeted their heads on streets as a warning. Iris Chang’s

The Rape of Nanking has the same

photo with a larger background behind the heads on page 113. Looking at the

photo, those who had experienced Nanking testified that the background is not

of Nanking.

This photo was identified as a Japanese soldier executing a Chinese. However,

the alleged Japanese soldier is swinging the sword down with one hand. This

is indeed Chinese way. The Japanese never swing a sword down with one hand,

but with both hands. It is clear that this was a Chinese prearranged

performance. The man with the sword appears in other forged photos, also.

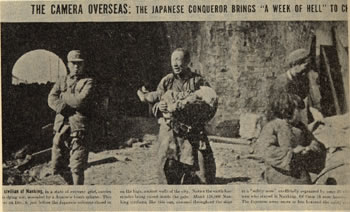

This photo is used as purported evidence of infant victims of the Nanking

Massacre and is displayed at the Nanking

Massacre Memorial

Museum in China. However, this photo was

not taken in Nanking, for the photo is from a postcard sold in China in war

days as the one taken at Tiyelien in Manchuria.

There was no custom of slaughtering infants even of the enemy throughout

Japanese history, although this custom frequently appears in Chinese

chronicles. Denialists suggest that this photo is in fact a picture of

victims of Chinese civil war.

It is well known in Japan

that General Iwane Matsui of the Japanese army saved from the battle a

Chinese infant who was found crying. He let his subordinate carry the child

on his back when marching into Nanking,

named her Matsuko, and continued to nurture the child.

This photo of a gibbeted head appeared in Life

magazine on January 10, 1938. The caption stated that the head was of an

anti-Japanese Chinese man and had been placed there on “Dcember

14, just before the fall of Nanking.” However, December 14 was not before the fall

of Nanking. The caption also gives the

impression that the Japanese military were responsible for this atrocity, but

in China

there were a lot of cases of gibbeted heads due to personal hatred or civil

war, and there is no positive proof that the Japanese were responsible for

these acts.

This photo from Life magazine on

January 10, 1938, was taken on December 6, 1937 and explained as a Chinese

man carrying his son who had been wounded in the Japanese bombing. This was

not a photo after December 13, 1937, the day of the fall of Nanking.

The soldier on the left wears a cap that looks Chinese. The movie, Battle of China, and others, used this

photo as a depiction of the Nanking Massacre.

Purported evidence of a Japanese public execution in Nanking.

However, the surrounding people wear summer clothes, so this photo is not

related to the Japanese occupation of Nanking,

which took place in winter. There was no custom of public execution in Japan after the 1870s, although it remained in

China

in the 1930s. Denialists allege that this was a prearranged pose set up by

the Chinese for propaganda purposes.

This photo is explained as an old woman who was killed by the Japanese

military and skewered with a pipe thrust into her vagina, without proof that

the criminal was really Japanese. This photo has no accompanying reliable

information about the evidence: who judged it and how. This kind of killing

by skewering was a Chinese practice frequently seen among the Chinese in

those days and in Chinese chronicles—not among the Japanese.

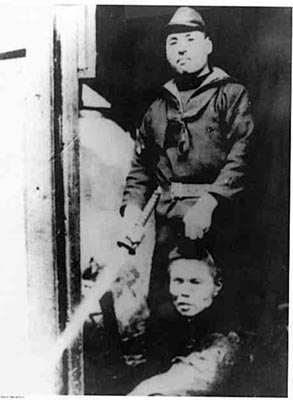

This photo is described as a Japanese sailor after beheading and used to show

a Japanese atrocity. However, the uniform of the man with a sword is

different from a Japanese sailor’s. And, if we look closer, the severed head

is so short-haired that the standing “sailor” could not possibly hold it up

by grabbing its hair. In addition, the part under the severed head is

blackened, which may cause us to speculate that this was actually a

touched-up photo of a live man with the area around his head blackened sitting

next to the sword-holding man. Denialists allege that this was a prearranged

pose set up by the Chinese for propaganda purposes.

This photo was taken in the ruins of Shanghai

by H.S. Wang, a Chinese American photographer, and first appeared in Life magazine on October 4, 1937. This

became one of the most influential photos to stir up anti-Japanese feeling in

the USA,

and is still used to show Japanese atrocities in relation to the Nanking

Massacre. However, a correspondent of the Chicago

Tribune News Service later presented other photos taken at the same hour

and same place showing evidence that this had been a staged photo: the baby

was brought there by the photographer to create a dramatic photo.

Lies and Propaganda

These forged photos

above were distributed by the Chinese Nationalist Party propaganda bureau to

enlist the support of the United States for their war against Japan. Theodore

H. White, who had been an adviser to the Chinese propaganda bureau,

confessed, “It was considered necessary to lie to it [the United States], to deceive it, to do anything to persuade America. . . . That was

the only strategy of the Chinese government. . . .” (In Search of History: A Personal

Adventure)

Historians say that the Chinese chronicles were the

history of those who deceived and of those who were deceived. The alleged

Nanking Massacre was one of their deceiving means.

See

more fake photos

|

The So-Called Nanking Massacre

was a Fabrication

The Japanese Military in Nanking (Nanjing) was Humane

The alleged massacre, which was said to have been

committed

by the

Japanese Military in Nanking, China, did not take place.

Those who committed atrocities were Chinese soldiers.

Reverend

Arimasa Kubo

(Japanese Christian pastor and non-fiction writer)

What is the Alleged Nanking

Massacre?

The alleged Nanking

Massacre, commonly known as the Rape of Nanking, is the name of a genocidal

war crime said to have been committed by the Japanese military in the city of

Nanking, the then capital of the Republic of China, after it fell to the

Imperial Japanese Army on December 13, 1937. There is a dispute about whether

it really occurred or not.

Massacre affirmationists claim that during the

occupation of Nanking, the Japanese army committed numerous atrocities such

as rape, looting, arson and the execution of prisoners of war and civilians.

They say that the Japanese massacred about 300,000 Chinese people in Nanking

during the six weeks after the Japanese occupation of the city. On the outer

wall of the Nanking Massacre Memorial Museum in China is written “300,000” as

the number of the massacre victims. Many Chinese children visit there every

year to be planted anti-Japanese feeling in their hearts.

Massacre denialists claim that newspapers, photos, documentary films, records

and testimonies in those days all tell the Nanking Massacre of 300,000 people, a large-scale massacre or even a

small-scale massacre, did not take place. According to denialists, the

so-called Nanking Massacre was a fabrication and false propaganda spread

by Chinese Nationalists and Communists for their political purpose.

Today, we have numerous reliable pieces of evidence showing that the massacre

did not actually occur. Firstly, I will give a brief explanation of what

actually occurred in Nanking, and then, show the details.

What Actually Occurred in Nanking

At the Battle of Shanghai in

1937, when the Chinese military of more than 30,000 soldiers attacked the

Japanese settlements in Shanghai, many people were killed, not only Japanese,

but also many Chinese and Westerners. That was the beginning of the Sino-Japanese

war. To stop the Chinese attack and the war, Japan decided to occupy Nanking,

the then capital of the Republic of China. During the battle, every civilian

who remained in Nanking took refuge in the Safety Zone, which was specially

set up within the walls of the city. The Japanese military did not attack it,

and no civilian was killed.

Until the time of the Japanese occupation of Nanking, the Chinese military

had committed numerous bad deeds such as plunder and rape among citizens. The

citizens who had abhorred them welcomed the entry of the Japanese military

into Nanking, giving cheers and rejoicing (see the picture at the top of this

page).

Just before the Japanese occupation, the population of the city was about

200,000. One month after the

occupation, many Chinese citizens came back to Nanking learning that peace

had returned, and the population increased to about 250,000. Newspapers

in those days had numerous photos of Chinese citizens who had come back to

Nanking and lived peacefully, buying, selling and smiling with Japanese

soldiers.

In the battle of Nanking, many Chinese

soldiers discarded their military uniforms to run away, killed Chinese

civilians to take off civilian clothes, and hid themselves among Nanking

citizens. Espy, the American vice-consul at Nanking, and others witnessed

these scenes. Those who massacred

Chinese people were in fact Chinese soldiers. The Chinese military in those days was rather a crowd of robbers, than

to be called a disciplined military. They plundered Chinese villages of

foods, raped women and burnt the villages. Civilians who were killed in and

around Nanking were mostly killed by the Chinese military. There are many

testimonies and evidence about it.

Furthermore, many of the Westerners, who took care of the Nanking

Safety Zone, sheltered Chinese military officers secretly, breaking the

agreement with the Japanese military to be neutral. Many of the Chinese soldiers raped

Chinese women at places, and did many other atrocities, putting them on an

act of the Japanese military.

The Westerners in Nanking repeatedly reported the alleged Japanese

atrocities, such as numerous rapes, killings and robberies to Western

countries (especially

to the USA) until January 4,

1938, for the Westerners had ever believed the atrocities were done by the

Japanese; however, on that day, the Chinese soldiers whom the Westerners had

sheltered were arrested by the Japanese military. The Westerners were so

embarrassed to see the Chinese soldiers confessing that they had done

those atrocities, and had blamed the Japanese military for their attacks.

The

New York Times reported it.

The same arrests

of Chinese soldiers took place on Jan. 25 and Feb 17, 1938, etc. After

those, the atrocities in Nanking stopped. People in Nanking got peace and

order. Most of the Westerners, too, stopped talking about Japanese

atrocities. Thus, the Chinese soldiers whom the Westerners sheltered were in

fact doing such atrocities in Nanking. The sheltered Chinese soldiers also had

told lies to the Westerners that the Japanese were doing various

atrocities at places, and the Westerners, believing their lies, had reported

those to the US, etc., and provoked strong anti-Japanese feelings there.

These

Westerners’ reports are often referred to still today as the evidence of

Japanese atrocities. However, they were thus not the evidence of Japanese

atrocities, but the evidence of the Chinese atrocities and their

anti-Japanese maneuverings. Other than those Chinese soldiers whom the

Westerners sheltered, there were also many other Chinese soldiers hiding in

the Nanking Safety Zone, wearing civilian clothes and hiding weapons to

prepare urban warfare. The Japanese military found out and arrested these

illegitimate soldiers. Rebellious ones were executed by the Japanese

military; however, these executions were recognized as legitimate under

international law.

It is also a fact that there were around ten or several tens cases of small

crimes such as plunder and rape committed by Japanese soldiers in Nanking.

However, these were similar to the crimes which soldiers of other countries

also committed in occupied territories, and the Japanese criminals were

strictly punished.

There were such things, but the Japanese military did not massacre anyone in

Nanking. The Japanese military rather

did many humane aid activities to Nanking citizens and POWs. There was no

single Chinese citizen who starved to death under the Japanese occupation.

Seeing these Japanese activities and being moved by them, there were even

Chinese POWs who later joined Wang Jingwei’s pro-Japanese government.

The following are the details.

********************

Evidence that the Japanese Military Did Not Massacre

Return of the Populace

The population of Nanking just before the Japanese occupation was

about 200,000. About a week before

the Japanese attack on Nanking, on November 28, 1937, the head of the Police

Department of Nanking, Mr. Wan, announced at a press conference for

foreigners, “About 200,000 people still live here in Nanking.” Five days

after the Japanese occupation, on December 18, 1937, the International

Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, which was a group of Westerners

remaining in Nanking, announced that the population of the city was about 200,000.

Later, on December 21, the Foreigners Association in Nanking referred to

200,000 as the population of Nanking.

How could the

Japanese kill 300,000 citizens in a city that held only 200,000 people?

One month after

the Japanese occupation, many Nanking

citizens who had escaped the city came back to Nanking, learning that

peace had returned, and the population increased to about 250,000. There is a

record that the Japanese troops distributed food to that number of citizens.

On January 14, 1938, about one month after the Japanese occupation, the

International Committee announced that the population of Nanking had increased to about 250,000.

The

Japanese military had published Good

Citizen Certificate to Nanking citizens from the end of December

1937 to January 1938 to distinguish them from Chinese soldiers hiding in

Nanking in civilian clothing. The total number of the certificates reached

about 160,000, although this figure does not include children under the age

of ten and old people above the age of sixty. Professor Lewis Smythe, who was

in Nanking as a member of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety

Zone, wrote in his letter to Tokuyasu Fukuda, a

probationary diplomat of the Japanese Embassy in Nanking, that according to

this figure, the population of Nanking was about 250,000-270,000.

Many Nanking

citizens thus came back to the city, and the population increased. Would the

citizens have come back to a city in which there had been a massacre?

Press Reports

On the day when the Japanese

troops entered Nanking, more than 100 press reporters and photographers

entered together with them. The press corps were not only from Japan, but

also from European and American press organizations, including Reuters and

AP. However, none of the press corps reported the occurrence of a massacre of

300,000 people. Paramount News (American newsreels) made films reporting the

Japanese occupation in Nanking, but did

not report the occurrence of a massacre.

The British newspaper North China Daily

News, which was published in China in English on December 24, 1937,

eleven days after the Japanese occupation of Nanking, carried a photo taken

in Nanking by their photographer. The photo was entitled “Japanese distribute

gifts in Nanking.” In the photo are Japanese soldiers distributing gifts, and

Chinese adults and children receiving the gifts and rejoicing. Is this the

scene of a massacre?

Radio Addresses

The Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek,

who had escaped from Nanking just before the attack by the Japanese military,

broadcasted radio addresses hundreds of times to the Chinese people until the

end of the Pacific War. He never

mentioned the Nanking Massacre even once. This is very unnatural—if the

mass slaughter really occurred.

Newspaper Photos

At the time of the Japanese

occupation of Nanking, a major Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, published many photos of Nanking. Five days after

the occupation the newspaper reported on the peaceful scenes of Nanking. In one of the photos, Japanese

soldiers are buying something from a Chinese without carrying their guns. In

another photo, Chinese farmers who returned to Nanking are cultivating their

fields. In others, a crowd of Chinese citizens are returning to Nanking

carrying bags, and Chinese adults and children wearing armbands of the flag

of Japan are standing around a street barbershop and smiling.

The Asahi Shimbun also reported

scenes of Nanking eight days after the occupation in an article entitled, “Kindnesses to Yesterday’s Enemy.” In

one of the photos, Chinese soldiers are receiving medical treatment from

Japanese army surgeons. In another, Chinese soldiers are receiving food from

a Japanese soldier. In other photos, Japanese soldiers are buying goods at a

Chinese shop, a Japanese officer is talking with a Chinese leader across a

table, and Chinese citizens are shown relaxing. Are these the scenes of a

massacre? Articles from other dates are similar, reporting that peaceful

Chinese living returned to Nanking. Many Chinese civilians came back to the

city; farmers began to cultivate their fields and merchants began to do

business again. How can we say there was a massacre in the city?

The sources of these photos are very clear. They can be seen at the National

Diet Library of Japan. We cannot deny that they were taken in Nanking just

after the Japanese occupation.

The Japanese Military Did Not Attack Civilians

Before the battle of

Nanking, the commander General Iwane Matsui ordered the Japanese army to be

very careful not to kill any civilians.

During the battle, every civilian took refuge in the Nanking Safety Zone,

which was specially set up to protect all the civilians of Nanking. The

Japanese army knew that many Chinese soldiers were also in the Zone;

nevertheless, the army did not attack it, and there were no civilian victims,

except for several who were accidentally killed or injured by stray shells.

This Nanking Safety Zone was managed by the International Committee for the

Nanking Safety Zone, which was a group of professors, doctors, missionaries

and businessmen from Europe and the USA. They did not leave Nanking before

the beginning of the battle, but chose to remain in the city. The leader of

the Committee was John Rabe, and after the Japanese occupation, he handed a letter of thanks to the commander of

the Japanese army. The following is an excerpt from his letter of thanks:

December 14,

1937

Dear commander of the Japanese army in Nanking,

We appreciate that the artillerymen of

your army did not attack the Safety Zone. We hope to contact you to make

a plan to protect the general Chinese citizens who are staying in the Safety

Zone. We will be pleased to cooperate with you in any way to protect the

general citizens in this city.

--Chairman of the Nanking International Committee, John H. D. Rabe--”

If the Japanese

military wanted to massacre every Nanking citizen, it would have been very

easily done if they only bombarded the Nanking Safety Zone, because it was a

narrow area and all civilians gathered there. The Japanese military did not

attack it, but rather protected all the people of the Zone.

The reason why the Japanese military attacked Nanking was similar to the

reason why the American and the allied militaries once attacked Baghdad of

Iraq at the Gulf War in 1991. The alliance wanted to get rid of the Iraqi

dictator who was doing bad things to neighboring countries. Similarly, Japan

wanted to get rid of Chiang Kai-shek’s dictatorship which was giving torments

to many Chinese people and also to Japan. General Matsui’s purpose of the war

was not to take the land, but to save Chinese civilians from his dictatorship

and from the Chinese civil war, killing among the Chinese themselves. Japan

wanted to establish in China a strong Chinese government not of communists,

not of Western powers, but of the Chinese people who were willing to build in

cooperation with Japan the great Asia which

would not be invaded by communists or exploited by Westerners. It was

impossible for such Japanese military to kill Chinese civilians.

Traditionally in Japan, Samurai warriors lived inside walls of castle, and

inhabitants like farmers and merchants lived outside the walls. Civilian

cities were not walled. War was a fight only among warriors, and they never

killed civilians. If a Samurai killed innocent civilian either in his land or

enemy’s land, the Samurai’s lord blamed him as against the Samurai spirit,

and punished him. While, in China, inhabitants like farmers and merchants

lived inside a walled city, and in wars the inhabitants inside were often all

slaughtered along with warriors. In Chinese chronicles, we often read such

massacres. The Chinese language has the word which writes slaughtering castle

and means slaughtering all people within the city. It was a Chinese culture.

The Japanese never had such a culture. Nanking was a walled capital city, and

the idea of massacring all inhabitants was Chinese, not Japanese.

Total Number of Buried Bodies

After the

battle of Nanking, the Japanese military entrusted the burial of the war dead

to the Chinese.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo Trial) used the

burial records of about 40,000 bodies

by the Red Swastika Society, a Chinese voluntary association in Nanking,

as evidence of killings of the Japanese military. The Tribunal also used the burial records of 112,267 bodies by the

Chung Shan Tang (Tsung Shan Tong), a 140-year-old charitable organization.

The combined total was about 155,000.

However, concerning the Chung Shan Tang, none of the documents which were

written by members of the International Committee in Nanking or the Japanese

authorities in Nanking mentioned that the Tsun Shan Tang was engaged in the

burial work. Kenichi Ara, a researcher of modern history, showed evidence in

an article of the Sankei Shimbun newspaper that the Chung Shan Tang’s

burial report of 112,267 bodies had been entirely forged and that they had

actually buried no bodies. The Chung Shan Tang’s report was a false one added

after the war to amplify the number of burials.

It was a fact that the Red Swastika Society engaged in the burial work. They

buried almost all the war dead in Nanking, and according to the Society, the

burials reached about 40,000. This is far from 300,000. In addition, these

40,000 were killed in battle, not in a massacre, because among the bodies were almost no corpses of women and children. This means that the Japanese military did

not massacre civilians. I will mention the details later.

Denial of Massacre in Testimonies

Shudo Higashinakano,

a professor at Asia University in Tokyo, published a compilation of the

testimonies of Japanese soldiers who had participated in the Nanking

operation in his book entitled, The

Truth of the Nanking Operation in 1937. In these testimonies, no Japanese

soldiers testified that there had been a massacre. For instance, Colonel Omigaku Mori stated, “I have never heard or seen any massacre in Nanking.”

Kenichi Ara, a researcher of modern history, published a compilation of the

testimonies of Japanese press reporters, soldiers and diplomats who had

experienced Nanking during the Japanese campaign. In these testimonies, also,

no one testified that there had been a massacre of civilians. Yoshio

Kanazawa, a photographer from the Tokyo

Nichinichi Shimbun newspaper, testified, “I

entered Nanking with the Japanese army and walked around in the city at

random every day, but I have never

seen any massacre nor heard it from soldiers or my colleagues. It is

impossible for me to say that there was a massacre. Of course, I saw many

corpses, but they were those killed in battle.”

Tokuyasu Fukuda, who was in Nanking as a Japanese

diplomat, testified, “It is a fact that there were crimes and bad aspects of

the Japanese military, but there was

absolutely no massacre of 200,000-300,000, or even 1,000 people. Every

citizen was watching us. If we had done such a thing (massacre), it would be

a terrible problem. Absolutely it is a lie, false propaganda.”

Kannosuke Mitoma, a press

reporter of the Fukuoka Nichinichi Shimbun newspaper, worked as the head of

the Nanking branch office at the time of the Japanese occupation. In those

days his daughter attended the Japanese elementary school in Nanking (from

the first grade to the fifth). She testified, “I used to play with neighboring Chinese children in Nanking, but I

have never heard even a rumor of the massacre.”

Humane Activities and Fellowship in Nanking

A chief of infantrymen

testified, “We defeated the enemy and saw thousands of them dead on the

ground of Nanking. But finding a Chinese soldier still alive, our captain

gave him water and medicine. The Chinese soldier folded his hands and said

“Xie xie” (Thank you) with tears welled up in his

eyes. In this way, our infantry

company saved 30-40 Chinese soldiers and let them go home. Among them

were many who cooperated with us and worked for us. When they had to part

from us, they were reluctant to leave, shed tears and then went home.”

A sergeant major of infantrymen testified, “On the way to Nanking, I was

ordered to stand as a guard having a rifle one night when I noticed a young

Chinese lady in Chinese dress walking toward me. She said in fluent Japanese,

‘You are a Japanese soldier, aren’t you.” And she continued, ‘I ran away from

Shanghai; other people were killed or got separated and I thought it would be

dangerous for me to be near the Chinese military, so I’ve come here.” “Where

did you learn Japanese?” said I, and she said, “I graduated from a school in

Nagasaki, Japan, and later, worked for a Japanese bookstore in Shanghai.” We

checked but there was nothing suspicious on her. And since we did not have

any translator, we decided to hire her

as a translator. She was also very good at cooking, knowing Japanese

taste, and turned on all her charm for all of us, so we made much of her. She

sometimes sang Japanese songs for us, and her jokes made us laugh. She was

the only woman in the military unit but made our hard march pleasant. Before

the beginning of our attack to the city of Nanking, the commander made her

return to Shanghai.”

A first lieutenant testified, “When we had just entered the Nanking Safety

Zone, every woman was dressed in rags with her face and all her skin dirtied

with Chinese ink, oil or mud to appear as ugly as possible. But after they got to know that the Japanese

soldiers were strictly maintaining military discipline, their black faces

turned to natural skin, and their dirty clothes turned to fine ones. Soon, I

became to come across beautiful ladies in the streets.”

Another soldier testified, “When I was washing my face in a hospital in

Nanking, a Chinese man came to me and said, “Good morning, soldier,” in

fluent Japanese. He continued, “I was in Osaka for 18 years.” I asked him to

become a translator for the Japanese army. He later went to his family, came

back and said, “I told my family, ‘The Japanese army have come. So, you are

now all safe.’” He cooperated

faithfully with the Japanese army for 15 months until we reached Hankou.”

If there had been a massacre of civilians in Nanking, it would have been

impossible for the Chinese man to work for the Japanese.

Naofuku Mikuni, a press reporter, testified, “Nanking citizens were generally cheerful

and friendly to the Japanese just after the fall of Nanking, and also in

August 1938 when I came back to Nanking.” He points out that if the Japanese

crime rate was very high, such cheerfulness would not have been seen in the

city.

Not only these Japanese persons, but also James McCallum, who was in Nanking as an American medical doctor,

wrote in his diary on December 31. 1937, “Today I saw crowds of people

flocking across Chung Shan [Zhongshan] Road out of the Zone. They came back

later carrying rice which was being distributed

by the Japanese from the Executive Yuan Examination Yuan.”

McCallum also wrote, “I must report a good deed done by some

Japanese. Recently

several very nice Japanese have visited the hospital. We told them of our

lack of food supplies for the patients. Today they brought in 100 shing [jin (equivalent to six kilograms)] of beans along with

some beef. We have had no meat at the hospital for a month and these gifts

were mighty welcome. They asked what else we would like to have.”

Are these the scenes of a

city in brutal massacre?

Chinese Soldiers Discarded Military Uniforms

Mochitsura Hashimoto, a Japanese soldier who fought

in the battle of Nanking near the Yangtze River, testified, “Though the

Chinese soldiers carried their rifles or machine-guns, none of them were in

regular military uniform.” Other veterans testified, “None of them showed

signs of surrender.” Therefore, the Japanese army had to continue to attack

them, and many of the Chinese soldiers were shot or drowned in the river.

However, pictures of these dead

soldiers in civilian clothing—who had been killed in battle—were later

used in the Western world as “evidence of the massacre of civilians.”

Many of the Chinese soldiers in Nanking discarded their military uniforms,

and became “illegitimate” combatants. F. Tillman Durdin, an American News

correspondent, wrote in his article in the New York Times on December 22, 1937, “I witnessed wholesale undressing of a [Chinese] army.... Many men

shed their uniforms.... Others ran into alleys to transform themselves into

civilians. Some soldiers disrobed completely and then robbed civilians of

their garments.” Durdin also wrote that Chinese soldiers who reached the

Yangtze River tried to escape using junks, but “many were drowned in periods

of panic at the riverbank.”

Japanese veterans testify that, when they entered Nanking, they saw

throughout the city piles of Chinese military uniforms that had been taken

off and abandoned on the ground.

Among the Chinese soldiers who discarded uniforms, those who ran away from

the battle fields were killed by the Japanese military, or by a “Chinese supervisory unit”—Chinese

soldiers who were ordered to kill any of their fellow soldiers trying to flee

from the battlefield. The US military and the Japanese military do not have

such a unit, but Chinese soldiers trying to escape from battle field were

killed by the supervisory unit who was waiting behind. These killed ones did

not wear military uniforms, but they were actually soldiers.

There were also Chinese soldiers who discarded military uniforms and killed

Chinese civilians to obtain civilian clothing and to hide themselves among

citizens. James Espy, the American vice-consul at Nanking, reported to the

American Embassy at Hankow concerning conditions before the fall of Nanking,

writing, “During the last few days some

violations of people and property were undoubtedly committed by them [Chinese

soldiers]. Chinese soldiers in

their mad rush to discard their military uniforms and put on civilian

clothes, in a number of incidents, killed

civilians to obtain their clothing.”

The Chinese military was basically a scratched-together army of hooligans,

having no military discipline or concept of international law. They were the

same as bandits. They did not protect Chinese civilians, but rather plundered

of them, set fire to houses, raped women and killed civilians. They did these

things also in Nanking, as we will see the details later.

Miner S. Bates and His Incorrect Reports

The first source who

reported the so-called "Nanking Massacre" to the world was not a

Chinese, but an American who was a supporter of the Chinese Nationalists.

Miner S. Bates (1897-1978), who was in Nanking as a leading member of the

International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone. He wrote on January 25,

1938:

“Evidence from

burials indicates that close to forty thousand unarmed persons were killed

within and near the walls of Nanking, of whom some 30 percent had never been

soldiers.”

The number of

the massacre victims was thus first claimed as about 40,000, not 300,000. The

number 300,000 is a so-called "Chinese figure," which means

enlarged.

Bates is still

told in the US as if he were a hero who protected Nanking civilians from the

Japanese massacre; however, it was not a fact. Bates was publicly a Christian

missionary and a university professor in Nanking; but in fact, it turned out

after the war that Bates had been an adviser to the Chinese Nationalist

Party. Bates was a part of the Chinese propaganda about how bad the Japanese

were. Bates was later decorated by Chiang Kai-shek for his

"contribution," for he himself wrote so in his personal history.

As I mentioned

earlier, the International Committee members living in Nanking repeatedly

blamed the Japanese military for many atrocities, such as rapes and lootings,

but those were actually committed by the Chinese soldiers harbored by the

members. On the other hand, only Bates reported the alleged Japanese

mass-killings of Nanking civilians.

Even the

spokesman of the Chinese nationalist party never mentioned the Japanese

massacre at their 300 times press interviews at Hankou for one year after the

Japanese occupation of Nanking. Bates was thus the only man who was eager to

try to insist the Nanking Massacre. The people who were or once were in

Nanking did not see any Japanese mass-killings of civilians, but it was

possible for Bates to let the people outside Nanking believe there had been

that massacre.

Different from

James Espy, who reported the Chinese atrocity of killing many civilians to

take civilian clothing, Bates never reported such a Chinese atrocity. He only

testified the Nanking Massacre allegedly committed by the Japanese. We have

to think that Bates' report was very biased, for he was secretly acting as a

part of the Chinese propaganda to spread how bad the Japanese military was.

Was the Nanking

Massacre that Bates insisted true? No. Firstly, Bates’ report of "40,000

unarmed persons were killed" was incorrect. That was his mistake or

willful lie. The number 40,000 was from the burial list of the Red Swastika

Society, a Chinese group, who buried almost all of

the war dead under the request of the Japanese military. According to the

list, they buried close to 40,000 bodies. This was the total number of all

who were killed in Nanking, except Japanese soldiers. Most of the bodies were

of armed Chinese soldiers, not “unarmed persons.”

In fact, in April 1938, that was four months after the

Japanese occupation, an officer from the Embassy of the United States in

Tokyo visited Nanking to hear from Bates detailed information about the

Japanese occupation. However, Bates did not say any word about the massacre,

for Bates could not tell about the massacre to the man who actually saw the

peaceful scenes of Nanking.

Bates also could

not prove the Japanese massacre of civilians when he was required to show

proof by Consul John M. Allison. There are many such things about Bates.

Prof. Shudo Higashinakano

of Asia University, who inquired the details, wrote, "I can't help being

surprised of Bates’ double-tongues."

Secondly, Bates

claimed, “some 30 percent (of the 40,000) had never been soldiers.” However,

Professor Tadao Takemoto (Tsukuba University) and Professor Yasuo Ohara (Kokugakuin University) point out that the "evidence

from burials" of the Red Swastika Society in fact contains only 0.3

percent of women and children. The burial list has the distinction of sex and

rough age. If the Japanese military killed many civilians, the percentage of

women and children must have been very high, yet it was actually almost none.

That means, the 40,000 bodies were armed Chinese soldiers, not civilians.

Bates’ Testimony: Truth or Lie?

Miner S. Bates also testified in the Tokyo Trial after World War II that he

had seen many civilian dead bodies lying about everywhere in his neighborhood

for many days in Nanking after its fall. Did he tell a fact?

No. According to

the Japanese newspaper Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun on December 26, 1937, which

reports when correspondents Wakaume and Murakami

visited Professor Bates at his official university residence on December 15,

two days after the fall of Nanking, Bates welcomed them in a good humor,

shook hands with them and said, “I am so happy that the orderly Japanese

military entered Nanking and peace has been restored to the city.” The

correspondents did not see in his neighborhood the “…many civilian dead bodies

lying about everywhere,” which Bates testified to have seen.

Yuji Maeda, a Domei Tsushin

correspondent who spent days in the Nanking Safety Zone like Bates did,

denies that there were massacred bodies as follows: “Those who claim that a

massacre took place in Nanking assert that most of the victims were women and

children. However, these supposed victims were, without exception, in the

Safety Zone and protected by the Japanese Security Headquarters. The Nanking

Bureau of my former employer, Domei Tsushin, was

situated inside the Safety Zone. Four

days after the occupation, all of us moved to the Bureau, which served both

as our lodgings and workplace. Shops had already reopened, and life had returned to normal. We were

privy to anything and everything that happened in the Safety Zone. No massacre claiming tens of

thousands, or thousands, or even hundreds of victims could have taken place

there without our knowing about it, so I can state with certitude that none

occurred. Chinese soldiers were executed, some perhaps cruelly, but those

executions were acts of war and must be judged from that perspective. There

were no mass murders of non-combatants.”

(World and Japan magazine issued by Naigai News Agency, #413,

April 5, 1984)

Not only these correspondents, but also Japanese veterans and other press

reporters testify that they did not see any massacred civilians in Nanking.

Correspondent Kondo of the Asahi

Shimbun newspaper testified about his experience in Nanking, “There was a

fierce battle at the Guanghua Gate. I saw corpses of both Chinese and

Japanese soldiers there, but I did not see any civilian corpses.”

Jiro Nimura, a Mainichi Shimbun

photographer, testified, “I climbed up a wall of Nanking and entered the city

with the 47th regiment. Inside the walls I saw only a few dead bodies.” And

Isamu Tanida, a staff officer of the 10th Army, testified, “On December 14,

the city was already quiet and I heard no shots there. In the afternoon I

walked around in the city taking some pictures, when I saw a few corpses of

Chinese soldiers only.”

A veteran of the 7th Regiment, which was assigned to sweep the Safety Zone,

testified that the regimental command had been, “Don’t kill citizens. Don’t dishonor the army,” and they had

followed this command. He testifies, “Absolutely there was no massacre.”

Thus, nobody saw the alleged massacred civilians inside the Safety Zone, as

well as outside it.

All the honest witnesses thus did know that there was no massacre by the

Japanese in Nanking. But only Bates, who was an adviser to the Chinese

Nationalist Party, was acting as a part of the Chinese lie that the Japanese

military was so bad.

Information Source of Durdin’s

Report

Miner S. Bates was an

information source for the press also. On December 18, 1937, the American

correspondent F. Tillman Durdin wrote in the New York Times, “all the alleys and streets were filled with

civilian bodies, including women and children.”

However, this

article was not what Durdin himself witnessed, for Durdin wrote, “Foreigners

who toured the city and saw that all the alleys and streets were...” Durdin

thus wrote what he had heard. Who were the “foreigners”? They were Rabe,

Bates, and other International Committee members; however, no one in Nanking

actually saw such civilian corpses in alleys and streets. So didn’t Durdin.

Durdin in fact wrote this article based on what he had heard from Bates, for

Bates drove Durdin to the harbor on December 15 to see him off, and Durdin

got on board a ship and left Nanking at 2:00 p.m. Bates later wrote in a

letter of April 12, 1938, that he had

given a memo about the incidents of Nanking to Durdin and other

correspondents on December 15. Durdin’s article was written according to this

memo that Bates handed him. Bates was a source of false information on the

alleged massacre of civilians in Nanking.

In 1938, the book entitled What War

Means written by H.J. Timperley was published. Timperley, who was not in

Nanking, but in Shanghai, wrote in the book sensationally about the massacre

of Nanking civilians. This book is famous for having given a strong influence

to the US public opinions. The information source of Timperley’s book was

also Bates, for Timperley wrote so in the book.

Timperley was

paid by the Chinese Nationalist Party. Zeng Xubai,

the chief of the China Information Committee, writes in his autobiography:

“Timperley was

an ideal man. Thus, we decide that our first step would be to make payment to

Timperley, and also through his coordination, to Smyth, and commission both

of them to write and publish two books for us as witnesses to the Nanking

Massacre…..We held discussions with Timperley, and he became our secret man

in charge of propaganda in America”

Bates and

Timperley in partnership were thus eager to drag the United States into their

war against Japan by telling how bad Japan was. Concerning the strategy of

the Chinese Nationalist Party, American journalist Theodore H. White, who had

been an adviser to the Chinese Nationalist propaganda bureau, confessed:

“It was considered necessary to lie to it [the United States], to deceive

it, to do anything to persuade America. . . . That was the only strategy

of the Chinese government. . . .” (In Search of History: A Personal Adventure)

Chinese Soldiers Killed by Chinese Supervisory

Units

The American correspondent

F. Tillman Durdin reported in the New

York Times that he had witnessed on December 15 a lot of bodies of dead

Chinese soldiers forming a small mound six feet high at the Nanking Yijiang gate in the north.

Concerning this mound of Chinese dead, Professor Tokushi

Kasahara interviewed Durdin on August 14, 1987. Durdin stated that the mound had been formed before the

Japanese military reached there, and that the Chinese soldiers had not

been killed by the Japanese military. He said, “The bodies were Chinese

soldiers who tried to escape.... I think that the mound of bodies had been

formed before the Japanese military occupied there. In that area there was no

combat of the Japanese military.”

According to

Professor Higashinakano, the bodies witnessed by

Durdin had been killed by the Chinese

supervisory unit that had been waiting behind to kill Chinese soldiers

trying to escape from the battlefield. The American or Japanese military

never have such a unit, but the Chinese military always had such a unit to

kill their fellow soldiers.

Professor Bunyu Ko at Takushoku

University in Tokyo estimated that throughout the Sino-Japanese war the

victims killed by such Chinese supervisory units had been more than those

killed by the Japanese military.

In Nanking also,

there were many Chinese soldiers who were killed by the Chinese supervisory

unit, not by the Japanese military. The casualties that Miner Bates and other

Committee members mentioned included such victims.

Only Legitimate Executions

When the defeat of the

Chinese military became definite in the battle of Nanking, Chinese soldiers

had three choices. The first was to surrender, and those who surrendered were

taken as POWs (prisoners of war). The second was to escape from Nanking. Those

who ran away were killed either by the Japanese military or the Chinese

supervisory unit. The third was to hide, wearing civilian clothes, in the

Safety Zone which had been specially set up inside the walls of Nanking for

civilians. Every Nanking citizen was taking refuge in the Safety Zone, and

many of the Chinese soldiers took this choice and hid themselves in the Zone.

After the fall of Nanking, the

Japanese military did a mop-up operation to find those Chinese soldiers

hiding in the Zone. Those who were caught and found hiding weapons were

executed. They were considered to have been preparing a street fighting or

guerilla activities. According to Professor Higashinakano,

the Japanese military executed several thousand such dangerous Chinese

soldiers. Some scenes of this execution were witnessed by both Western and

Japanese press reporters.

The question is whether or not the executions by the Japanese military were

legally justifiable. Legitimate combatants who have become POWs are under the

protection of international conventions, which govern their treatment. They

are immune from capital punishment unless they violate laws or regulations.

The killing of such POWs without legitimate cause would indeed constitute an

unlawful massacre. However, the

Chinese soldiers who were arrested in the Safety Zone were not entitled to

the privileges of POWs because they did not meet any of the four

qualifications of belligerents as stipulated in the Hague convention of 1907.

These four qualifications are:

1. To be commanded by a person responsible for his subordinates

2. To have a fixed distinctive emblem recognizable at a distance

3. To carry arms openly

4. To conduct their operations in accordance with the laws and customs of war

Those who did not satisfy these qualifications were deemed to be illegitimate

combatants and were not eligible for protection under international law. This

principle was upheld in the 1949 Geneva Convention on the treatment of POWs.

The execution of such illegitimate combatants was customarily practiced in

each country, and the execution was thought to be legitimate. Unfortunately,

the Chinese soldiers did not have the wit to follow this international law.

Massacre denialists thus claim that the execution of the Chinese soldiers,

who were in civilian clothing and hiding weapons, was legitimate.

The Japanese military executed these Chinese soldiers; however, the Japanese

military did not execute all the captured Chinese soldiers. They employed many of them as a labor force,

and they numbered about 10,000 by the end of February 1938. Some of them were

registered as civilians.

POWs Not Executed

Massacre affirmationists

often refer to the division commander Kesago

Nakajima’s diary, in which is written that Nakajima “thought about disposing

7,000-8,000 prisoners of war at Xianho Gate”

according to the military policy, “Accept no prisoners.” However, it was only

a plan. There are in fact records showing that the 7,000-8,000 POWs about

whom Nakajima wrote were not killed but sent to the concentration camp in

Nanking. It is also known that Kesago Nakajima was

later removed from his post because he had been found appropriating the

equipment of the residence of Chiang Kai-shek in Nanking for his own use.

The records also show that the

concentration camp received about 10,000 POWs in total, including the

prisoners sent by Nakajima. Many of the 10,000 POWs were later released, hired as coolies or sent to

the concentration camp in Shanghai. Nearly 2000 of them became soldiers for

Jingwei Wang’s pro-Japanese government. One of these was Qixiong

Liu, who had been hiding in the Nanking Safety Zone, was caught as a POW and

used as a coolie for a while. Later he became the commander of a brigade for

Wang’s pro-Japanese government.

Many Japanese soldiers testify that “Accept no prisoners” always meant “Unarm them and let them go home.”

They actually did so when there was no need to send them to a concentration

camp. Staff officer Onishi said, “They could go home walking. There never was

any military order or divisional order to kill POWs.”

Japanese Lieutenant General Yasuji Okamura once wrote his surmise based on

what he had heard from his staff officers in Shanghai. “It is true that tens

of thousands of acts of violence, such as looting and rape, took place

against civilians during the assault on Nanking.... (and) front-line troops

indulged in the evil practice of executing POWs on the pretext of (lacking)

rations.”

This description is also often referred to by massacre affirmationists;

however, Okamura was not in Nanking and his surmise was based on a report he

heard in Shanghai. Since the Westerners of the International Committee, who

were in Nanking, reported only 450 cases of atrocities such as looting, rape

and murder committed by the Japanese military, Okamura’s surmise of “tens of

thousands of acts of violence” was clearly based on an incorrect rumor.

It is a fact, as Okamura wrote, that some officers thought to execute POWs on

the pretext of lacking rations; however, the POWs were not executed after

all.

Nobody in Nanking Witnessed 300,000 Victims

Reverend John Magee, who was in Nanking before and during

its Japanese occupation for years, filmed scenes of Nanking, and the film

is often referred to in relation to the alleged Japanese atrocities. However,

Magee’s film shows no scenes of

clearly massacred victims. The captions are alleged atrocities of the

Japanese, but the movie has no scenes of Japanese soldiers executing POWs, no

scenes of thousands of dead bodies—in fact, the movie shows mostly scenes of

living people.

John Magee also wrote about some alleged Japanese atrocities; however, most

of those were hearsay. So was the famous horrible incident in the following.

“On December 13,

about 30 soldiers came to a Chinese house at #5 Hsing Lu Koo in the

southeastern part of Nanking, and demanded entrance. The door was opened by

the landlord, a Mohammedan named Ha. They killed him immediately with a

revolver and also Mrs. Ha, who knelt before them after Ha’s death, begging

them not to kill anyone else. Mrs. Ha asked them why they killed her husband

and they shot her dead. Mrs. Hsia was dragged out from under a table in the

guest hall where she had tried to hide with her 1-year-old baby. After being

stripped and raped by one or more men, she was bayoneted in the chest, and

then had a bottle thrust into her vagina. The baby was killed with a bayonet.

Some soldiers then went to the next room, where Mrs. Hsia’s parents, aged 76

and 74, and her two daughters aged 16 and 14 were. They were about to rape

the girls when the grandmother tried to protect them. The soldiers killed her

with a revolver. The grandfather grasped the body of his wife and was killed.

The two girls were then stripped, the elder being raped by 2-3 men, and the

younger by 3. The older girl was stabbed afterwards and a cane was rammed in

her vagina. The younger girl was bayoneted also but was spared the horrible

treatment that had been meted out to her sister and mother. The soldiers then

bayoneted another sister of between 7-8, who was also in the room. The last

murders in the house were of Ha’s two children, aged 4 and 2 respectively.

The older was bayoneted and the younger split down through the head with a sword.

“

Magee heard

about this crime from the 7-8 year old girl who had been bayoneted but

survived and told this whole story two weeks after the crime. Magee wrote

that he had recorded this story, adding some “corrections” to what the girl

told him with the help of her relatives and neighbors. Magee thought that

these “soldiers” had been Japanese; however, they could not be Japanese, but Chinese.

Magee wrote that this had happened on December 13, but on December 8 every

citizen had been already forced to move to the Safety Zone by the Chinese

army, and was inside the Zone. The family in the story was outside the Zone,

and it was most dangerous and highly unlikely that they were outside it on

December 13 when the Japanese military entered the city. It is thus very

likely that the crime was actually

committed before December 8 or 13 by Chinese soldiers. In addition, the

practice of thrusting items into females vaginas was typically Chinese. Such

a practice often appears in Chinese chronicles. The Japanese never had such a

custom.

The murder case witnessed by Magee himself was, as he testified in the Tokyo

Trial, only one: a Japanese

soldier shooting a Chinese who had begun to run away when questioned about

his name and identity by the Japanese soldier. The Japanese soldier was

searching Chinese soldiers in mufti (ordinary clothes), and such a killing is

recognized as legitimate under international law. In other words, Magee did not see 300,000 or even

40,000-60,000 massacred victims in his all days in Nanking.

According to Magee, the cases which he himself witnessed other than the

above-mentioned killing were only one rape and one rubbery. The rest were all

hearsay. The alleged rape he witnessed was that he had seen a Japanese

soldier coming toward a man’s wife; however, Magee did not actually see a

rape. The Japanese soldier might have come to question the woman or her

husband. The alleged robbery was that Magee had seen a Japanese soldier

coming out of a house with an icebox in his hands. In other words, Magee did not personally see any horrible

crimes committed by Japanese soldiers in Nanking.

Nanking was not filled with Japanese atrocities.

Low Crime Rate of Japanese Soldiers

It is a fact that Japanese

soldiers committed a relatively small number of crimes in the city. On Dec.

18, 1937, five days after the fall of Nanking, the commander of the Japanese

army, General Iwane Matsui, held with his whole army a memorial service to

express condolences to both the Chinese and the Japanese war dead. In his

speech he scolded his men for what he had heard about crimes of rape and

looting committed by Japanese soldiers in the city. Matsui said:

“A group of

soldiers dishonored our Imperial Army by performing outrageous conduct. What

the hell have you done? What you did was unworthy of the Imperial Army. From

now on, keep military discipline strictly and never treat innocent people

cruelly. Remember it is the only way to console the war dead.”

It is noteworthy

that General Matsui never mentioned the occurrence of a massacre. Later, he

testified in the Tokyo Trial on Nov. 24, 1947:

“After the fall

of Nanking, some young officers and men committed atrocities, for which I

deeply feel sorry. However, I never

heard or saw in Nanking a large scale massacre or atrocities such as the

ones the prosecution insists upon, and it was never reported when I was in

Shanghai, either.”

Thus, it is a

fact that some crimes were committed by Japanese soldiers in Nanking.

However, the crime rate was much lower than that of cities occupied by the

Chinese or the Russians. One may say that the Japanese crimes in Nanking were

in fact similar to the ones committed by soldiers of the American occupation

forces in Japan after the US-Japan war. Japanese press reporters who were in

Nanking testify, “Nanking citizens were cheerful.” If the crime rate was very

high, that could not have been possible.

Yasuto Nakayama, a staff officer of the Japanese army in Nanking, testified

in the Tokyo Trial:

“I heard the

alleged Nanking Massacre story for the first time after the war ended. I

think we need to consider this in four parts. The first one is massacre of civilians, which I believe

never occurred. The second one is massacre of POWs, which I believe never

occurred, except the ones mistakenly told. The third one is infringement on

foreign rights and interests as well as their property, which I think

occurred in part, but it is not clear still today which committed it, the

Japanese or the Chinese. And the fourth ones are rape to women and looting to

citizens, which I think occurred on a small scale and I deeply feel sorry for

them.”

Hirotsugu Tsukamoto, a Japanese judicial officer who was in charge of

punishment of the military criminals in Nanking, testified:

“After the entry into Nanking, unlawful acts were committed by Japanese

soldiers and I remember having examined these cases. I think that there were four or five officers involving in the

above cases I disposed, but the rest were cases mostly sporadically committed

by the rank-and-file. The kinds of crimes were chiefly plunder and rape,

while the cases of theft and injury were few. And to the best of my knowledge

I remember that there happened few cases that resulted in death. I remember

that there were a few murder cases, but have no memory of having punished incendiaries or dealt with mass

slaughter criminals.”

According to the testimony of this judicial officer, it seems that the

crimes of Japanese soldiers in Nanking numbered around ten, several tens or

so at the most. Of course, these Japanese criminals were strictly punished.

This crime rate was relatively low, compared with the one of other countries’

soldiers in occupied territories of World War II.

Truth About the Alleged Atrocities

of the Japanese

In February, 1938, the

International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, which consisted of

Westerners living in Nanking, forwarded to the Japanese Embassy a report of

about 450 cases of crimes allegedly committed by Japanese soldiers in

Nanking, such as murder, rape, and looting. This report is often referred to

as showing Japanese atrocities. How can we think of this?

Most of these 450 cases were based on hearsay, with the exception of only a

few cases that the Committee members themselves witnessed or directly

confirmed. And even if these 450 cases were all true, murder cases numbered only 49, which are far different from 300,000,

the alleged number of massacre victims. In other words, first of all we can

say that this report proves a large-scale massacre did not take place in

Nanking.

As for the 49 murder cases of the report, the ones which were witnessed by

the Committee members themselves number only 2, which were both legitimate,

such as killing when a Japanese military policeman found and shot a

suspicious man who did not answer to his question and suddenly ran away. None

of the Committee members in Nanking witnessed illegitimate murders.

As for rape cases, Professor Tadao Takemoto and Professor Yasuo Ohara point

out:

“How many cases

of rape (including attempted) were reported in the documents by the Safety

Zone Committee? The total number was 361. Among them, there were only 61

cases which definitely clarified who witnessed the cases, or who heard and

reported them. Among these cases, only seven cases were clarified to be

crimes committed by Japanese soldiers, and were notified to the Japanese Army

in order to disclose the fact and to capture the suspects.... Furthermore, as

reported in the article in the Chicago Daily News dated February 9, 1938, the

Japanese Army investigated about the

seven cases and severely punished the criminals. The punishment was so

severe that some complaints were expressed among the soldiers.”

Tokuyasu Fukuda, who had been in Nanking as a

probationary diplomat of the Japanese embassy, testified about the actual

situation of this International Committee and their report of 450 cases, as

follows:

“The nature of

my duties required me to visit the office of the International Committee

almost everyday. At the office, I saw Chinese men come in one after

another, saying, ‘Japanese soldiers are now raping 15-16 year old girls

in such and such a place,’ or ‘Japanese soldiers are committing looting at a

house of such and such a street,’ etc.. Rev. Magee, Rev. Fitch and several

others were typing these charges immediately to report to their countries. I

warned them again and again, ‘Wait,

please. Do not report them without confirming.’ Occasionally, I hurried

with them to the scene of the rape, looting, etc., but found nothing, nobody

living there, and no trace of it; I experienced such cases often. I believe

that Timperley’s book What War Means (1938)

was written based on such unconfirmed reports.”

In

those days, Japan was not at war against Western countries yet; however, many

Westerners including those living in Nanking were basically hostile to Japan.

The Westerners in Nanking were even sheltering Chinese military officers

secretly, breaking their promise with the Japanese military, without knowing

that the Chinese men whom they were

sheltering committed numerous crimes such as rape, looting and murder among

Chinese civilians and then blamed the Japanese for their attacks. I will

mention the details later. The Westerners thus sent any information of

alleged Japanese atrocities without confirming or any proof to stir up

anti-Japanese feeling in Western countries.

Atrocities Committed by Chinese

Soldiers

Many Japanese veterans testify that those who

committed “rape, looting, arson and murder” were not the Japanese military,

but rather the Chinese military. A sergeant major testified, “We reached a

Nanking suburb, where the troops of Chiang Kai-shek once had been. Hearing

from the inhabitants, we got to know the

inhabitants had been plundered of all their food and household goods by the

Chinese army, who also had forced the village men work very hard. How

poor the people of such a country are!”

Itaru Kajimura, a

Japanese second lieutenant, wrote in his diary on January 15, 1938—when the

battle of Nanking had already ended and his unit was stationed near

Shanghai—that a nearby Chinese village had been attacked by 40-50 remnants of

a Chinese defeated army. The village people had come and asked his unit for

help. Kajimura and about 30 men hurried there with

the village people, but it was after the enemy had already committed looting,

rape, and murder in the village and gone. Kajimura

wrote, “Chinese civilians, who were

attacked by Chinese soldiers, asking Japanese soldiers for help. What a

contradiction! This one thing shows what Chinese soldiers are.” He also

wrote that the village people had been “very reluctant” to part from the

Japanese unit.

F. Tillman Durdin, an American news reporter who covered Nanking, wrote,

“(From December 7 the Chinese army)

set fire to nearly every city, town, and village on the outskirts of the city

(Nanking). They burned down...entire villages...to cinders, at an

estimated value of 20 to 30 million (1937) US dollars.” Durdin also wrote

that the damage from the fire was more than that from the Japanese air raid.

James Espy, the American vice-consul at Nanking, reported to the American

Embassy at Hankow concerning conditions before the fall of Nanking, writing,

“During the last few days some

violations of people and property were undoubtedly committed by them [Chinese

soldiers]. Chinese soldiers in

their mad rush to discard their military uniforms and put on civilian

clothes, in a number of incidents, killed

civilians to obtain their clothing.”

Those civilians who were killed by such Chinese soldiers were many, and that

the “civilian victims,” whom Westerners in Nanking alleged the Japanese

military had killed, in fact included such civilians.

Kannosuke Mitoma, a press

reporter, testified, “After entering Nanking, I interviewed a Chinese husband

and his wife who had been in the Nanking Safety Zone since before the

Japanese occupation. They said, ‘‘When

Chinese soldiers were in the city, they came to refugees everyday

to plunder food, commodities and every cent of money. They took away

young men for labor and young women to rape. They were the same as bandits.

And in this Safety Zone there still are bad Chinese men.’”

General Matsui also testified, “There were quite a few atrocities committed

by the Chinese in Nanking. If these were all attributed to the Japanese

military, it would distort facts.”

Anti-Japanese Maneuvers by Hiding Chinese Soldiers

A Westerner in Nanking sent

a letter to the US in December 1937 as alleged Japanese atrocities as

follows:

“More than ten

thousand persons have been killed in cold blood, Most of my trusted friends

would put the figure much higher… Able German colleagues put the cases of

rape at 20,000. I should say not less than 8,000 and it might be anywhere

above that. On university property alone, I have details of more than 100

cases and assurance of some 300. You can scarcely imagine the anguish and

terror. Girls as low as 11 and women as old as 53 have been raped on

university property alone. On the seminary compound 17 soldiers raped one

woman successively in broad daylight.”

Many such

letters were sent to the US in those days. These are still used today as

evidence of Japanese atrocities. However, it was until January 4, 1938. Until

then, all the Westerners had ever believed that the Japanese were doing the

atrocities, but on that day the New

York Times reported:

“American